- Home

- Tracy Chevalier

Reader, I Married Him: Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre Page 8

Reader, I Married Him: Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre Read online

Page 8

I had a husband.

I was secure.

Was he in love with me? Was I in love with him? I have not the slightest idea. I knew I excited him, I know that I was excited, and flattered. I knew excitement and flattery led to marriage. And I wanted marriage.

When I made those promises, I meant to keep them, I really did. I meant to try, I really did.

After all, I was secure. Why rock the boat?

But the boat was already holed below the waterline. I found that out the moment he took a bottle of gin from his suitcase on arriving at our honeymoon hotel in Virginia, where liquor was prohibited.

If poverty and shame had toughened me, I was still a little soft-centred.

Marriage to an occasionally violent drinker baked me hard.

I went on trying, all the same. I left. I returned. Tried harder. Left again. In the course of it, I discovered that I had something that could attract the attention of other men and that was my escape route.

I did not go back again.

Oh, don’t look at me like that, with scorn and the advantage of hindsight; look at me and judge me from a time when women had so few options. It was much harder for us then. I was a divorced woman. I lacked security again and worse now, I lacked respectability.

So, to hang with it. I looked elsewhere, loved and was loved, seduced and betrayed. I should have been more careful of my reputation. That came to matter, years later and far more than I had bargained for, when I thought I had buried my past, and they exhumed it. Now I still believed in marriage and craved security, but I craved respectability more. So that is what I sought.

Reader, I . . .

No white velvet, candle-lit church, society column report this time. A register office and a blue coat.

I had broken up his dull marriage, but did I love him?

I was very fond of Ernest. He was kind. Good company. He had a respectable history, money though not riches.

Did he love me? I think he did.

At the least we suited each other and we were content. Is that happiness?

We moved to London and up in the world. I entertained with purpose. I had style and that impressed him. I was secure and felt it, in a way I never would again. If only it had remained there.

But then, introduced by mutual friends, we met. It was a private weekend though it still felt rather awkward. Formal. I was to learn before long that that was normal. It never quite goes.

I had a bad cold.

Ernest was beside himself, as excited as a child. He revered, admired, respected—what is the exact word for the way an Englishman views royalty, especially his future monarch? All the people we had come to know were the same but I, as an American, could never fully understand, let alone feel that way. If I had I might have trodden more warily. I had been raised to respect other people’s cultures but I could never believe, as I think my husband truly did, that different blood ran in his veins and in that of all royalty. And so, although naturally I was polite—I had been taught my manners—I broke protocol, I spoke before I was spoken to, said what I thought, was forthright. And it did not seem to shock him; on the contrary, he seemed to find it refreshing. The Prince liked straight talking, because he never got it.

I understood little of this at first, and later I scarcely thought about it. On that weekend ours was a casual, social encounter and, as I wrote to Aunt Bessie, it was most unlikely that we would meet him again.

I forget who it was warned me that “Royalty offers friendliness—but never friendship.” They were right. I certainly saw the ruthlessness with which he could sever even a close and longstanding relationship that had become boring or that he wanted to replace with something new and more amusing. I was warned.

But you see, what came my way was so much worse.

Everything was my fault, of course, everyone knew it, everyone blamed me. No one blamed him. But I was not the one who fell in love. I did not lose all reason, control, proportion; I did not throw away everything, everything else for . . .

For?

The world well lost for love?

He never doubted it.

Lost? No. It was not lost; he gave it away, he rejected and abandoned it. He turned his back.

He abdicated.

And all for love.

He abdicated the ultimate status. He abdicated Title. Country. Friends. Family.

Respect. Reverence. Deference. Safety. Security.

Security.

And all for love.

Think about that.

I do, every single day, though it has become easier. For years after it happened there was no room in my head for anything else, it was so shocking. It was, it still is, unimaginable.

Yes, but he did it, and for me. If I had been ruthless then, if I had turned my back on him, if I had clung instead to the security I enjoyed with Ernest. Who was still my husband.

If. If. If.

David was cowardly about getting rid of those he no longer wanted, always making others speak, write, reject, on his behalf. If I had made my husband take every phone call and pass on the message that I would never speak to him again, what would he have thought?

What was I? Weak? Flattered?

Yes.

I did not care about the status and the deference. That is God’s truth.

The title I might have had? HRH?

A little. He cared about it more.

Did I care about him? Want him?

Yes.

No.

Did I love him?

Yes.

But never in the way that he loved me, obsessively, to the exclusion of everyone and everything else. He made life difficult. He thought nothing of the trouble he caused, nothing of how I had to pacify Ernest, when he turned up without notice at our flat and stayed until two in the morning. As it went on the obsession grew. He became possessive. He once said, “I want to inhabit you, have all of you,” and that was terrifying.

I loved his company. We were easy together. I adored dancing with him. I was interested in what made him tick.

I was puzzled by him.

“Sometimes I think you haven’t grown up where love is concerned.” I wrote that to him and it was true. He never grew up. He was always a child. A boy.

I felt sorry for him—indeed, for all of his family. That is no sort of life, you know.

I am old now and David is dead. I miss him dreadfully because he became my whole life. My only life. We spent so many years together in exile, and every, every time I looked at him, I saw a man who thought the world well lost for love.

He clung to me. He followed me everywhere. He would look around a roomful of people and if he did not see me at once, there was panic in his eyes, like a child who loses sight of his mother.

He telephoned me day and night, sometimes half a dozen times. He neglected everything else for me. He filled the flat with flowers, and I love flowers. He spent his fortune on jewels for me, and I love jewels. But what are gifts? Was he trying to buy me with them? I did not love him more because I loved his flowers and his diamonds.

People who are so comprehensively in love often want to dominate and overpower, but David was far too weak a man for that. Yet out of his desperate passion, careless of everyone and everything else, he also parted me from what I knew and loved, everything familiar and dear and sure. He took the ground from under my feet, and I had not been sure of firm ground for so very long. The only thing left to me was Aunt Bessie, my link with childhood and my growing up. With America—those other worlds. David became very fond of Aunt Bessie.

What he did was the very last thing I ever wanted but no one believed me then or does so now. He was the King and greatly loved. He had the world at his feet and the people held him in their hearts and he threw it all away. He gave up the throne for me. Can you imagine how that made me feel? Yet I wonder if he had ever really wanted it. The work bored him; he hated the stuffiness and the pomp that surrounded it. He would not miss any of it.

Bu

t it never crossed his mind that when he gave it all up, he would also lose what he had always cared most about, until he met me—his family and his country. England was his home and so much besides. And knowing it, how could they have behaved as they did? They barred him from their hearts and from returning to live at home. They gave him a royal title with one hand, and refused one to me with the other, knowing that that would hurt and demean him most of all.

He loved his mother, dearly, dearly, but she never believed it. He spent his life trying to win her approval, but he never could. What he did for love of me was the hardest blow of all for her. How did I ever find myself coming between such a mother and son? How was I ever so blind and foolish as to involve myself in any of it?

His mother blamed me for everything. I was the scheming adventuress. The gold-digger. They believed I only wanted him because of what else I would get at the same time. They never understood that I wanted neither.

Be careful of what you wish for. But I was not the one who wished for it.

And love?

I came to love him because I was all he had, because he loved me, because we were trapped together, because he was a child, because he had lost everything else, because . . .

Was that the right sort of love? No. Was it enough for me? No.

Ernest left because there was no other way out—Ernest, that good, loyal, loving, unimaginative, put-upon man.

The night I sat and listened to the wireless, hearing David explain that he was abdicating because he could not face being King without having the woman he loved at his side, I wept more bitterly than I had ever wept. It was the worst night of my life. I had nothing left, no husband, no home, no reputation. I had only this man who clung to me so desperately, and the hatred of half the world.

We were sent into exile and led futile lives there.

If I had known . . .

But in my heart, I think I had known too well.

Be careful what you wish for.

Was he happy? Was I? Did we make the best of it?

Yes.

No.

Everything comes at a price, especially love.

I wore couture. Pale blue crêpe and a halo hat.

I am going out to walk in the garden with the dogs. I love their sweet, ugly, snuffling faces. They are all I have to love now and they love me in return.

If I die before them, who will love them so well? If they die before me, I will have nothing.

How little any of it seems to matter now.

Even this . . . that Reader, I married him.

THE MIRROR

FRANCINE PROSE

READER, I MARRIED HIM.

It turned out the sounds I heard coming from the attic weren’t the screams of Mr. Rochester’s mad wife Bertha. It wasn’t the wife who burned to death in the fire that destroyed Thornfield Hall and blinded my future husband when he tried to save her.

After we’d first got engaged, he’d had to admit that he was already married, and we’d broken off our engagement. He’d asked me to run away with him anyway. Naturally, I’d refused.

But later, after we were properly married, he insisted that it hadn’t happened that way. It turned out there had been no wife. It turned out that it had been a parrot, screaming in the attic. The parrot had belonged to his wife. She had got it in the islands, where she had also contracted the tropical fever that killed her. She’d died long before I came to work for him as a governess. That was never Bertha, in the attic.

Mr. Rochester couldn’t bring himself to get rid of the parrot. He had the servants take care of it, because his wife Bertha had loved it, and because it was pretty. But its cries drove the whole household mad, so they shut it up in the attic. He was sad the parrot died in the fire—but no one said the parrot had set the fire, the way they said his wife did.

And the madwoman who sneaked around the house at night, ripping up the wedding veil in which I was to be married to Mr. Rochester? Attacking one of the guests! That was not his wife either. That was a lunatic from the village who somehow got past the servants and stalked the dark house, wreaking havoc.

At that time I was very principled, very sensitive about being lied to, perhaps because I’d been called a liar at an earlier point in my life.

I said I remembered that when Mr. Rochester and I almost got married the first time, several trustworthy people had testified that his wife was still living. Upstairs.

He said, Obviously, they got it wrong. Was I calling him a liar?

Reader, you are probably thinking that nothing like this would ever happen to you. If you were pretty sure that a man’s wife had still been alive when you met, and that she’d gone mad, and that he had her shut up in the attic, and that she died in a fire, you would probably stick to your guns. You might not marry him, after that.

If you’re wondering why I did, possibly you are forgetting what he said to me in Chapter 27, the speech that goes on for pages and pages, during which he says everything that a poor orphan governess could possibly want to hear, everything that every woman wants to hear: pages and pages of passionately confessing to the growth of his obsession with me, the history of his love.

“I used to enjoy a chance meeting with you, Jane, at this time: there was a curious hesitation in your manner: you glanced at me with a slight trouble—a hovering doubt: you did not know what my caprice might be—whether I was going to play the master and be stern, or the friend and be benignant. I was now too fond of you often to stimulate the first whim; and, when I stretched my hand out cordially, such bloom and light and bliss rose to your young, wistful features, I had much ado often to avoid straining you then and there to my heart.”

Even if I’d known how things would turn out, how could I resist that?

And of course we eventually had our dear son, who was also named Edward, and whom I cherished and loved very much. And I think my husband did too, especially when the injuries he’d sustained in the fire were corrected, and he was finally able to see our child.

Mr. Rochester and I went into couples therapy. I’m not sure that I trusted the therapist, Dr. Collins. But since Mr. Rochester knew everyone in the area, since he was the lord of the manor, in attitude and in fact, I let him pick the therapist, though I knew I probably shouldn’t.

Dr. Collins assumed we were there to talk about how we were coping with my husband’s blindness, but that wasn’t the problem, at all. In fact we had found a doctor who said he could restore much of my husband’s sight.

It turned out: I had some crazy ideas about a mad first wife trapped in the attic.

The doctor produced a document saying that Madame Bertha Mason Rochester had died in Jamaica some years before I came to work as a governess for the man who was now my husband.

That seemed like a strange thing for a therapist to do. But it settled things, you could say. We moved on to other subjects.

It seemed to me that in therapy sessions my husband and I talked entirely too much about my history and my problems and not enough about whether or not the first Mrs. Rochester was dead or alive before I met my husband. I don’t believe we talked enough about who sneaked into the house that night and slashed my wedding veil to ribbons.

Though maybe I was just being stubborn. I’d always been a stubborn girl. Stubbornness and anger had extricated me from many unfortunate places.

At some point, during these early days, my husband took me to a petting zoo not far from where we’ve rebuilt an updated Thornfield Hall. (Fortunately, my husband had excellent insurance, and there was my long-delayed inheritance from my uncle.)

At the zoo there was a parrot.

My husband stood me a bit roughly in front of the parrot’s cage, put his strong masculine hands on my shoulders and said, Isn’t that what you heard, Jane?

No, I said. Actually, it wasn’t.

Soon after that, my husband told the therapist there was something he wanted to mention. A story I’d told him about my past. I’d been locked by some evil people in a

room where my uncle had died, and I’d been terrified by the idea that I’d seen his ghost.

Did the doctor think that a young person who so powerfully imagined something like that was likely to grow up into a woman who imagined that someone had stolen into her room and slashed up her wedding veil? Wasn’t it possible that I could have done it myself—sleepwalking, it could have been?

The doctor asked me if I had a history of sleepwalking.

No, I said. But, mostly to make conversation, I did mention that it was very common among the girls at Lowood, the hellish school I’d gone to, where they punished the girls so cruelly and severely.

I should never have mentioned Lowood. That got my husband started.

Did Dr. Collins realise that Jane had gone to a school where the girls were so badly abused that several of them died? Couldn’t that sort of experience have affected a person forever?

Well, of course it had affected me. It would affect anyone. But Mr. Rochester and I had chosen to agree that my marrying him would be the happy ending, the reward and the consolation that would make the past recede forever.

I couldn’t understand why my husband would have wanted me and a therapist to think that I was unstable, possibly even mad. I’d seen the film in which Charles Boyer does something similar to Ingrid Bergman, but there was an unsolved murder and some hidden jewels in that film, and there wasn’t anything like that, not with us.

Maybe my husband was still annoyed by my stubborn refusal to agree that the screams I had heard were the voice of a parrot. It would have been in my interest for it to have been a parrot, because it had turned out to be in my interest that his first wife had burned up in the fire. I would be lying if I didn’t admit I felt a bit guilty about how I’d benefited from her death. So I should have been eager to think she’d died of tropical fever in Jamaica.

Ultimately, I couldn’t understand why my husband would want the mother of his son to have the reputation of being mentally ill. Unless this was part of an evil pattern, an elaborate psychosexual drama that my husband was playing out.

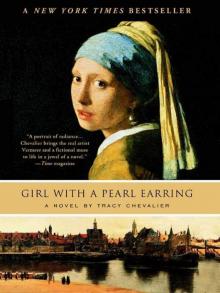

Girl With a Pearl Earring

Girl With a Pearl Earring A Single Thread

A Single Thread Reader, I Married Him: Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre

Reader, I Married Him: Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre The Last Runaway

The Last Runaway Burning Bright

Burning Bright Remarkable Creatures

Remarkable Creatures At the Edge of the Orchard

At the Edge of the Orchard The Virgin Blue

The Virgin Blue The Lady and the Unicorn

The Lady and the Unicorn Falling Angels

Falling Angels New Boy

New Boy Reader, I Married Him

Reader, I Married Him Girl with a Pearl Earring, The

Girl with a Pearl Earring, The