- Home

- Tracy Chevalier

A Single Thread Page 3

A Single Thread Read online

Page 3

Violet did not hate men, and had not been entirely man-free. Two or three times a year, she had put on her best dress – copper lamé in a scallop pattern – gone alone to a Southampton hotel bar, and sat with a sherry and a cigarette until someone took interest. Her “sherry men”, she called them. Sometimes they ended up in an alley or a motor car or a park; never in his room, certainly not at her parents’. To be desired was welcome, though she did not feel the intense pleasure from the encounters that she once had with Laurence during the Perseids.

Every August Violet and her father and brothers had watched the Perseid showers. Violet had never said anything to her father during those late nights in the garden, watching for streaks in the sky, but she did not really like star-gazing. The cold – even in August – the dew fall, the crick in the neck: there were never visions spectacular enough to overcome these discomforts. She would make a terrible astronomer, for she preferred to be warm.

The Perseid showers she remembered best were in August 1916, when Laurence had got leave and come to see her. They’d taken a train out to Romsey, had supper at a pub, then walked out into the fields and spread out a rug. If anyone happened upon them, they could be given a mini-lecture by Laurence about the Perseids, how the earth passed in its orbit through the remnants of a comet every August and created spectacular meteor showers. They were there in the field to watch, merely to watch. And they did watch, for a short while, on their backs holding hands.

After witnessing a few meteors streak across the sky, Violet turned on her side so that she was facing Laurence, her hipbone digging into a stone under the blanket, and said to him, “Yes.” Though he had not asked a question aloud, there had been one hanging between them, ever since they had got engaged the year before.

She could feel him smile, though she couldn’t see his face in the dark. He rolled towards her. After a while Violet was no longer cold, and no longer cared about the movement of the stars in the sky above, but only the movement of his body against hers.

They say a woman’s first time is painful, bloody, a shock you must get used to. It was nothing like that for Violet. She exploded, stronger it seemed than any Perseids, and Laurence was delighted. They stayed in the field so long that they missed any possibility of a train back, and had to walk the seven miles, until a veteran of the Boer Wars passed them in his motor car, recognised a soldier’s gait, and stopped to give them a lift, smiling at the grass in Violet’s hair and her startled happiness.

Only a week later they received the telegram about George’s death at Delville Woods. And a year later, Laurence at Passchendaele. He and Violet had not managed to spend more time properly alone together, in a field or a hotel room or even an alley. With each loss she had tumbled into a dark pit, a void opening up inside her that made her feel helpless and hopeless. Her brother was gone, her fiancé was gone, God was gone. It took a long time for the gap to close, if it ever really did.

A few years later when she could face it, she tried to experience again what she’d had with Laurence that night, this time with one of George’s old friends who had come through the War physically unscathed. But there were no Perseids – only a painful awareness of each moment that killed any pleasure and just made her despise his rubbery lips.

She suspected she would never feel pleasure with her sherry men. She had laughed about them with scandalised girlfriends, for a time; but some of her friends managed to marry the few available men, and others withdrew into sexless lives and stopped wanting to hear about her exploits. Marriage in particular brought many changes to her friends, and one was donning a hat of conservatism that made them genuinely and easily shocked and threatened. One of those sherry men could be their husband. And so Violet began to keep quiet about what she got up to those few times a year. Slowly, as husbands and children took over, and the tennis games and cinema trips and dance hall visits dried up, the friendships drifted. When she left Southampton there was really no one left to regret leaving, or give her address to, or invite to tea.

“Violet, where have you gone?” Tom was studying her over the remains of his chips.

Violet shook her head. “Sorry – just, you know.”

Her brother reached over and hugged her – a surprise, as they were not the hugging sort of siblings. They walked back to Mrs Harvey’s, where his motor car was parked. Violet stood in the doorway and watched his Austin hiss away through the wet street, then went upstairs. She had thought she might cry when finally alone, in her shabby new room, with a door she could shut against the world. But she had cried her tears out on the trip from Southampton. Instead she looked around at the sparse furnishings, nodded, and put the kettle on.

Chapter 3

VIOLET HAD NOT REALLY understood how hard it would be to get along on her own on a typist’s salary. Or she had, but vowed to manage anyway – the price she paid for her independence from her mother. When she’d lived with her parents, she handed over almost two-thirds of her weekly salary to help with the running of the household, keeping five shillings back for her own expenses – dinner, clothes, cigarettes, sixpenny magazines – and putting another few shillings in the bank. Over the years her savings had gradually built up, but she assumed she would need them for her older years when her parents were gone. She had to eat into them more substantially than she’d expected to pay for the deposit on her lodgings in the Soke, and for some bits and pieces to make the room more comfortable. Her mother had plenty to spare in the Southampton house, but Violet knew better than to ask. Perhaps if she were moving to Canada to find a husband, Mrs Speedwell would have been willing to ship furniture thousands of miles. But sending anything twelve miles up the road was an affront. Instead Violet had to scour the junk shops of Winchester for a cheap bedside table when there was a pretty rattan one sitting in her old bedroom, or a chunky green ashtray rather than an almost identical one in the Southampton sitting room, or a couple of chipped majolica plates for the mantelpiece when her mother had any number of knick-knacks in boxes in the attic. It had not occurred to her to take such extras when she moved out, for she had never had to make a strange room into a home before.

Violet was still earning thirty-five shillings a week at the Winchester office, the same as her Southampton salary. It was considered a good one for a typist – she had been at the company for ten years, and her typing was fast and accurate. It had felt generous when she lived at home; she could have a hot dinner most days and not think too hard before buying cigarettes or a new lipstick. But it was not a salary you could easily live on alone; it was rather like a pair of ill-fitting shoes that could be worn, but that pinched and rubbed and left calluses. Now that Violet had to survive on it she understood that, proud as she had been to earn and contribute to the running of the house, her parents must have regarded what she handed over almost as pocket money.

The same amount she’d given to her parents now went to her landlady, and it only covered breakfast; she paid for and cooked her own supper, and she had to pay for laundry and coal – things she’d taken for granted at home. Whenever she left the house she seemed to spend money – just little bits here and there, but it added up. Living was a constant expense. Violet could no longer put aside any money to save. She had to learn to make do, and do without. She began wearing the same clothes over and over, and washing them under the tap to avoid an excessive laundry bill, mending tears and hiding worn patches with brooches or scarves, knowing that whatever she did would never refresh the shabbiness. Only new clothes could do that.

She stopped buying magazines and papers, relying on O and Mo’s cast-offs, and did not replace her lipsticks. She began to ration her cigarettes to three a day. Many evening meals consisted of sardines on toast or fried sprats rather than a chop, for meat was too dear. Violet was not keen on breakfast – she would have preferred toast and marmalade – but since she was paying for it she forced herself to eat the poached egg Mrs Harvey served every morning, afterwards arriving at work faintly queasy. She took herself

to the cinema every week – her one indulgence, which she paid for by going without a meal that day. The first film she saw in Winchester was called Almost a Honeymoon, about a man who had to find a woman to marry in twenty-four hours. It was so painful she wanted to leave halfway through, but it was warm in the cinema and she could not justify sacrificing a meal only to walk out early.

Every Sunday she took the train to Southampton to accompany her mother to church, the money for the ticket coming from her slowly diminishing savings. It would never have occurred to Mrs Speedwell to offer to pay. She never asked Violet about money, nor about her job nor Winchester nor any aspect of her new life, which made a two-way conversation difficult. Indeed, Mrs Speedwell just spent the afternoons complaining, as if she had been saving up all of her grievances for the few hours her daughter was with her. If Tom and Evelyn and the children weren’t there, Violet almost always made an excuse and took an earlier train back, defiant and guilty in equal measure. Then she would sit in her room reading a novel (she was making her way through Trollope, her father’s favourite), or go for a walk in the water meadows by the river, or catch the end of Evensong at Winchester Cathedral.

Whenever she walked through the front entrance below the Great West Window and into the Cathedral, the long nave in front of her and the vast space above bounded by a stunning vaulted ceiling, Violet felt the whole weight of the nine-hundred-year-old building hover over her, and wanted to cry. It was the only place built specifically for spiritual sustenance in which she felt she was indeed being spiritually fed. Not necessarily from the services, which apart from Evensong were formulaic and rigid, though the repetition was comforting. It was more the reverence for the place itself, for the knowledge of the many thousands of people who had come there throughout its history, looking for a place in which to be free to consider the big questions about life and death rather than worrying about paying for the winter’s coal or needing a new coat.

She loved it for the more concrete things as well: for its coloured windows and elegant arches and carvings, for its old patterned tiles, for the elaborate tombs of bishops and kings and noble families, for the surprising painted bosses that covered the joins between the stone ribs on the distant ceiling, and for all of the energy that had gone into making those things, for the creators throughout history.

Like most smaller services, Evensong was held in the choir. The choir boys with their scrubbed, mischievous faces sat in one set of stall benches, the congregants in the other, with any overflow in the adjacent presbytery seats. Violet suspected Evensong was considered frivolous by regular church goers compared to Sunday morning services, but she preferred the lighter touch of music to the booming organ, and the shorter, simpler sermon to the hectoring morning one. She did not pray or listen to the prayers – prayers had died in the War alongside George and Laurence and a nation full of young men. But when she sat in the choir stalls, she liked to study the carved oak arches overhead, decorated with leaves and flowers and animals and even a Green Man whose moustache turned into abundant foliage. Out of the corner of her eye she could see the looming enormity of the nave, but sitting here with the boys’ ethereal voices around her, she felt safe from the void that at times threatened to overwhelm her. Sometimes, quietly and unostentatiously, she cried.

One Sunday afternoon a few weeks after the Presentation of Embroideries service, Violet slipped late into the presbytery as a visiting dean was giving the sermon. When she went to sit she moved a kneeler that had been placed on the chair, then held it in her lap and studied it. It was a rectangle about nine by twelve inches with a mustard-coloured circle like a medallion in the centre surrounded by a mottled field of blue. The medallion design was of a bouquet of branches with chequer-capped acorns amongst blue-green foliage. Chequered acorns had been embroidered in the four corners as well. The colours were surprisingly bright, the pattern cheerful and un-churchlike. It reminded Violet of the background of mediaeval tapestries with their intricate millefleurs arrangement of leaves and flowers. This design was simpler than that but nonetheless captured an echo from the past.

They all did, she thought, placing the kneeler on the floor and glancing at those around her, each with a central circle of flowers or knots on a blue background. There were not yet enough embroidered kneelers for every chair, and the rest had the usual unmemorable hard lozenges of red and black felt. The new embroidered ones lifted the tone of the presbytery, giving it colour and a sense of designed purpose.

At the service’s end, Violet picked up the kneeler to look at it again, smiling as she traced with her finger the chequered acorns. It always seemed a contradiction to have to be solemn in the Cathedral amidst the uplifting beauty of the stained glass, the wood carving, the stone sculpture, the glorious architecture, the boys’ crystalline tones, and now the kneelers.

A hovering presence made her look up. A woman about her age stood in the aisle next to her, staring at the kneeler Violet held. She was wearing a swagger coat in forest green that swung from her shoulders and had a double row of large black buttons running down the front. Matching it was a dark green felt hat with feathers tucked in the black band. Despite her modish attire, she did not have the appearance of being modern, but looked rather as if she had stepped aside from the flow of the present. Her hair was not waved; her pale grey eyes seemed to float in her face.

“Sorry. Would you mind if I—” She reached out to flip over the kneeler and reveal the dark blue canvas underside. “I just like to look at it when I’m here. It’s mine, you see.” She tapped on the border. Violet squinted: stitched there were the initials and a year: DJ 1932.

Violet watched her gazing at her handiwork. “How long did it take you to make it?” she asked, partly out of politeness, but curiosity too.

“Two months. I had to unpick bits a few times. These kneelers may be used in the Cathedral for centuries, and so they must be made correctly from the start.” She paused. “Ars longa, vita brevis.”

Violet thought back to her Latin at school. “Art is long, life short,” she quoted her old Latin teacher.

“Yes.”

Violet could not imagine the kneeler being there for hundreds of years. The War had taught her not to assume that anything would last, even something as substantial as a cathedral, much less a mere kneeler. Indeed, just twenty-five years before, a diver, William Walker, had been employed for five years to shore up the foundations of Winchester Cathedral with thousands of sacks of concrete so that the building would not topple in on itself. Nothing could be taken for granted.

She wondered if the builders of the Cathedral nine hundred years ago had thought of her, standing under their arches, next to their thick pillars, on top of their mediaeval tiles, lit by their stained glass – a woman in 1932, living and worshipping so differently from how they did. They would not have conjured up Violet Speedwell, that seemed certain.

She put out a hand as “DJ” set her kneeler on a chair and made to move off. “Are you a member of the Cathedral Broderers?”

DJ paused. “Yes.”

“If one wanted to contact them, how …”

“There is a sign on the notice board in the porch about the meetings.” She looked at Violet directly for a moment, then filed out after the other congregants.

Violet did not intend to look for the notice. She thought she had set aside the kneelers in her mind. But several days later, out for a walk by the Cathedral, she found herself drawn to the notice board and the sign about the broderers, written in careful copperplate like her mother’s handwriting. Violet copied down a number for Mrs Humphrey Biggins, and that evening used her landlady’s telephone to ring.

“Compton 220.” Mrs Biggins herself answered the telephone. Violet knew immediately it wasn’t a daughter, or a housekeeper, or a sister. She sounded so much like Violet’s mother in her better days that it silenced her, and Mrs Biggins had to repeat “Compton 220” with increased irritation until she eventually demanded, “Who is this? I will not tolera

te these silences. I shall be phoning the police to report you, you can be sure!”

“I’m sorry,” Violet stumbled. “Perhaps I have the wrong number” – though she knew that she did not. “I’m – I’m ringing about the kneelers in the Cathedral.”

“Young lady, your telephone manner is dreadful. You are all of a muddle. You must say your name clearly, and then ask to speak to me, and say what your call concerns. Now try it.”

Violet shuddered and almost put down the telephone. When the Speedwells first had a telephone installed, her mother had given her lessons in telephone etiquette, though she had often put off potential callers herself with her impatient manner. But Violet knew she must persist or she would never have her own kneeler in Winchester Cathedral. “My name is Violet Speedwell,” she began obediently, feeling like a small child. “I would like to speak to Mrs Biggins with regard to the embroidery project at the Cathedral.”

“That’s better. But you are ringing very late, and at the wrong time. Our classes finish shortly for the summer and don’t resume until the autumn. Miss Pesel and Miss Blunt need time over the summer to work on designs for the next batch.”

“All right, I’ll ring back then. Sorry to have troubled you.”

“Not so hasty, Miss Speedwell. May I assume you are a ‘Miss’ Speedwell?”

Violet gritted her teeth. “Yes.”

“Well, you young people are far too quick to give up.”

It had been a long time since Violet had been called a young person.

“Now, do you know how to embroider? We do canvas embroidery for the cushions and kneelers. Do you know what that is?”

“No.”

“Of course you don’t. Why do we attract so many volunteers who have never held a needle? It makes our work so much more time-consuming.”

“Perhaps you could think of me as a blank canvas, with no faults to unpick.”

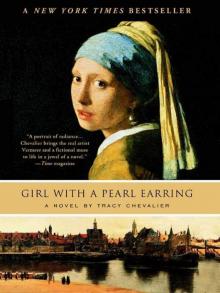

Girl With a Pearl Earring

Girl With a Pearl Earring A Single Thread

A Single Thread Reader, I Married Him: Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre

Reader, I Married Him: Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre The Last Runaway

The Last Runaway Burning Bright

Burning Bright Remarkable Creatures

Remarkable Creatures At the Edge of the Orchard

At the Edge of the Orchard The Virgin Blue

The Virgin Blue The Lady and the Unicorn

The Lady and the Unicorn Falling Angels

Falling Angels New Boy

New Boy Reader, I Married Him

Reader, I Married Him Girl with a Pearl Earring, The

Girl with a Pearl Earring, The